A number of the posts that I’ve done here at Tor.com—from Oz to Narnia to Disney retellings to what ABC would like you to believe are the “real” stories of Once Upon a Time—have featured fairylands and fairies in one way or another. So, the powers that be at Tor.com and I thought it might not be a bad idea to explore the lands of fairy tale just a little bit more, looking at various fairy tales and their tellers and retellers through the centuries, in no particular order, including medieval tales, Victorian tales, and modern retellings.

And although I said “no particular order,” it’s probably not a bad idea to start with the woman who gave us the term “contes des fees,” or fairy tales, Marie-Catherine Le Jumel de Barneville, Baroness d’Aulnoy, better known to English readers as Madame d’Aulnoy.

Determining the facts of Madame d’Aulnoy’s life can be a trifle difficult, in part because some documents have vanished, in part because the good baroness did not, shall we say, enjoy a reputation for strict honesty, and in part because she was frequently the target of various allegations and rumors, partly as counterattacks against her—alleged—involvement in multiple plots to condemn various male enemies to death.

She was apparently born sometime in the year 1650. Her family was wealthy and privileged, and d’Aulnoy seems to have had ample time to indulge a love for reading and stories. When still a teenager, she was married off to a much older man, Francois de la Motte, Baron d’Aulnoy. The marriage was not, to put it mildly, a success; only four years into the marriage, Madame d’Aulnoy was taking various lovers and busily attempting to accuse her husband of high treason against the king. In turn, her husband accused two men associated with her of high treason. Baron d’Aulnoy survived by fleeing Paris; the other two men were executed. At this point, Madame d’Aulnoy apparently decided that travel might be fun.

I say “apparently,” since most scholars and editors have questioned the veracity of Madame d’Aulnoy’s accounts of her next few years, on the rather unkind basis that all of the truthful, verifiable stuff seems to have been directly plagiarized from other accounts, and that the much more interesting unplagiarized sections cannot be independently verified. As her Victorian British editor, Anne Thackeray Ritchie, herself a writer of fairy tales, tactfully put it, “…it is difficult to tell whether they are a real history or the divagations of a fanciful imagination longing for adventure and excitement.” One French editor, Jean-Francois Dreux du Radier, did manage to put a positive spin on the inability to authenticate virtually anything unique written by d’Aulnoy, by noting that d’Aulnoy’s books at least offered anecdotes and observations found in no other books. Fiction, then and now, has its benefits.

Despite these doubts, it does seem possible that she spent the next several years travelling, if rather less possible that—as she later hinted—she worked briefly as a secret agent. It also seems more than possible that she did, indeed, fall in love frequently, or at least had a number of affairs. Her memoirs also mention a few children, not all, apparently, fathered by her husband. One daughter—if she existed—may have settled in Spain, perhaps explaining d’Aulnoy’s interest in the country.

Eventually, all of this—except the sex—seems to have lost its charms. At some point around 1690, Madame d’Aulnoy returned to Paris (or, simply confirmed that she’d never actually left), where she set up a glamorous and popular literary salon. Salons, at the time, were still relatively new and trendy in France (they had been more or less invented in Italy) and largely served as places for middle and upper class women to pursue intellectual interests and education. If Madame d’Aulnoy had not exactly done everything she claimed to have done, she was extremely well read, and by all accounts an outstanding conversationalist, well versed in another recent trend: folk tales, a part of entertainment at the salons.

Her salon was established during yet another turbulent period in French history. (I say yet another, since it sometimes seems difficult to find any period in French history that cannot be described as “turbulent.”) France had at least enjoyed a more or less stable monarchy under the reign of Louis XIV, the Sun King, since 1638, but that enjoyment came at the cost of very high taxes used to support Louis XIV’s many wars and extensive building projects. The wars had a purely human cost as well: Madame d’Aulnoy and the guests she welcomed to her salon must have personally met several men later killed or wounded in various battles.

As Anne Thackeray Ritchie would later put it, “Perhaps, too, people were not sorry to turn away from the present, from the disasters in which the reign of Louis XIV came to a close, and to take to stringing marvels and wonders on to old springs and threads that belonged to a world which they could govern and fashion to their fancy.” But escapism and the ability to control their folklore-inspired characters—in an early form of fanfic—was probably only one of the motivations behind the tales, which frequently feature subtle and not-so-subtle criticisms of tyranny and enforced social roles.

Direct criticism of Louis XIV, the Sun King, after all, could lead to very direct death by beheading. Criticizing evil fairies who just happened to be making outrageous demands (high taxes), imprisoning or exiling people on mere whims or because their noses were too long (from the point of view of aristocrats) or forcing people to live in a place of beauty they secretly detested (a feeling many nobles had about Louis XIV’s grand palace at Versailles), was more or less safe. Especially if these criticisms happened in salons somewhat safely located outside Versailles. I say more or less, since many of the witty, brilliant writers and conversationalists from the salons ended up exiled or imprisoned or executed anyway, but more or less. For most of the fairy tale writers.

Along with others, Madame d’Aulnoy took distinct advantage of these possibilities, using her tales to comment obliquely on court life in Versailles and (as far as we can tell) her own experiences, specifically focusing on the intrigues and dangers of court life. A courtier in a tale alternatively titled, in English, either “Fair Goldilocks” or “Beauty with the Golden Hair” is imprisoned not just once, but twice, on the basis of nothing more than malicious gossip—something d’Aulnoy had witnessed and gossiped about. Meanwhile, the courtier’s king, convinced that he’s not handsome enough for his wife, accidentally takes poison instead of a beauty potion. In an ending that smacks of both wish fulfillment and warning, the king’s self-esteem issues lead to his death—allowing the falsely imprisoned courtier to ascend to the throne.

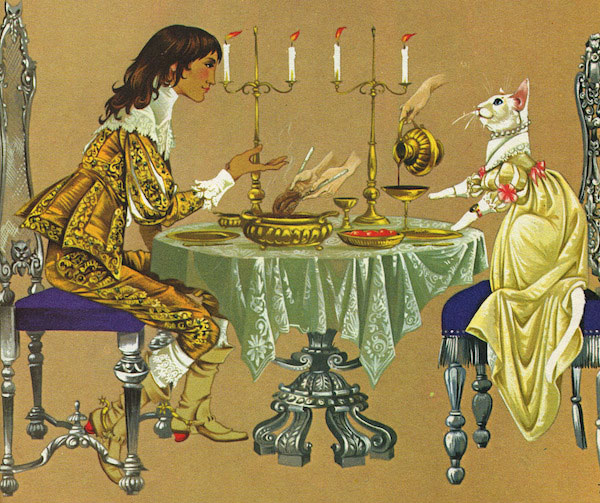

Other stories feature easily tricked nobles and royals, isolated by manners and convention, eager to believe lies and flattery from sycophants. In “The Blue Bird,” a clever woman manipulates a king suffering from clinical depression by pretending to be equally depressed and mourning herself—thus able to understand his grief. After their marriage, d’Aulnoy comments, “Apparently, one needs only to determine a person’s weakness in order to gain his trust and do just what one wishes with him.” The voice, perhaps, of experience.

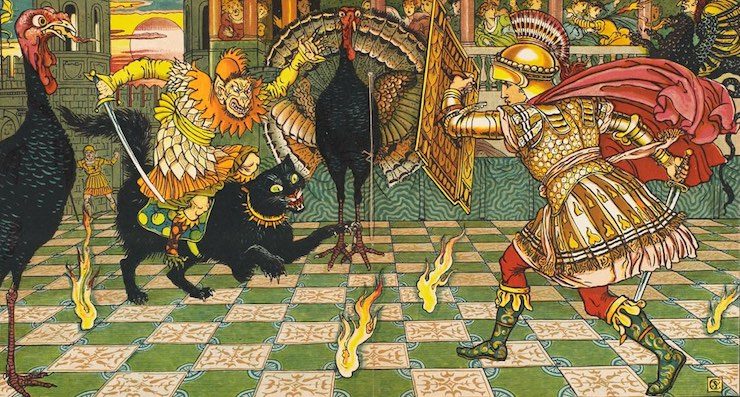

That tale continues with noble after noble—including, in a nice touch, the woman herself—finding themselves tricked as the characters play on one another’s emotions and manipulate each other for personal gain. In a sideplot, the most manipulative, deceitful royals are overthrown by an angry mob, before fleeing to another country where they find themselves manipulated and tricked again. On the other hand, a somewhat less manipulative royal—somewhat—is able to retain control of his country even after his transformation into a bird, though once he, too, starts attempting to deceive people in hopes of regaining his humanity, he finds himself deceived and drugged in turn. Meanwhile, right after directly witnessing a palace revolution, the protagonists remain focused on their personal life, and not governing, with one royal abandoning her new government to go chase after a potential husband, and another focused on delaying his marriage instead of a government that he’s already abandoned for years—probably explaining why, just a couple of pages later, his servants eagerly accept bribes. Even with its trappings of fairy tale and enchantment and magic, “The Blue Bird” paints a sordid picture of court life.

Other tales emphasize just how quickly circumstances—and thus monarchies—could change. Over and over again, monarchs find themselves facing invasions—and losing. D’Aulnoy ends her version of Beauty and the Beast, “The Ram,” with the stern warning: “Now we know that people of the highest rank are subject, like all others, to the blows of fortune,” illustrating this with the sudden death of a king. (A heroic captain also dies offscreen.) Another king and queen prove to be such terrible rulers that they are driven away from the kingdom within the first two sentences of the story. Not surprisingly, the entire family—king, queen, and most of their daughters—turn out to be deeply dysfunctional. The king and queen continually try to abandon their daughters in the middle of nowhere; the older sisters brutally beat their younger sister, and once again, pretty much everyone is easily manipulated.

D’Aulnoy’s tale of a cross-dressing heroine, Belle-Belle, or the Chevalier Fortune, starts with similar themes: a king and his sister swiftly forced out of their palace through war, a protagonist easily manipulated (it’s a theme) into situations intended to kill her. But a side moment looks at another issue: the plight of an aristocratic family unable to pay its tax bill, another situation familiar to d’Aulnoy’s audience after the years of wars under Louis XIV. A later scene features a king taking full credit for the dragon slaying done by others, echoing whispered accusations of the Sun King’s tendency to take full credit for the achievements of others.

But Madame d’Aulnoy’s criticisms of French royalty and aristocrats only went so far—in part because she presumably wanted to keep her head on her shoulders, and in part because of her own belief in the inherent superiority of France, a theme that appears again and again in her tales. “The Island of Happiness,” for instance, spends its introductory paragraphs explaining just how rough and primitive and obsessed with bear-hunting the Russians are, before continuing on to a story that has almost nothing to do with Russia or bears.

And she had other concerns besides veiled criticisms of royalty: enforced marriages (she was firmly of the belief that women should be allowed to turn down suitors); sexual harassment (things do not go well for nearly anyone, male or female, who continues to press unwanted romantic and/or sexual attentions on other characters); overly elaborate court fashions that, she claimed, were used only to conceal an underlying ugliness, and frequently failing at that; and untrustworthy servants.

Speaking of servants, D’Aulnoy is also not overly kind to peasants in her tales—when, that is, they even appear. She knew that peasants existed, and occasionally used them as plot points (as in the palace revolution in “The Blue Bird”) but for the most part, the only good, trustworthy peasants in her tales are royals or fairies in disguise. Though, for all her focus on royals, she knew they could be overthrown, and the aristocrats and royalty in her tales who ignore a peasant’s cry for help generally face considerable consequences for their indifference.

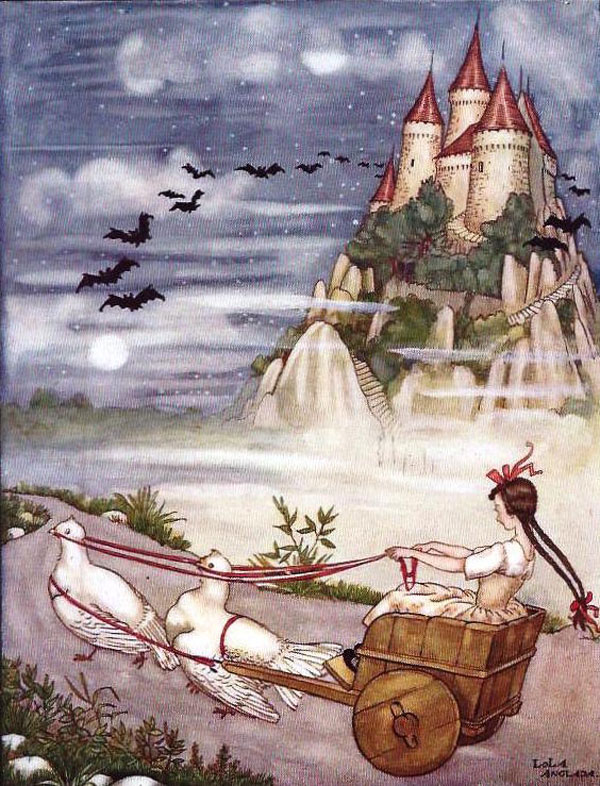

D’Aulnoy published sixteen of her fairy tales in Les Contes des Fees, or Tales of Fairies—that is, fairy tales. Another collection gathered together seven longer, more intricate tales. She also published popular novels and “histories,” which, however inaccurate, were popular. She was honored in her own time as one of the very few women elected to the Accademia Galiliena, an academic honor granted in acknowledgement of her “histories.” Her example inspired other women, and a few men, to publish their own fairy tales, helping to create the literary fairy tale. Most of d’Aulnoy’s tales were eventually translated into English; Andrew Lang, for one, was impressed enough to include five of her stories in his original The Blue Fairy Book—a near record for a single author. Elements of her tales also may have seeped into other cultures, and accidentally into some of the “oral, peasant” tales gathered by the Grimms, a few of which seem to have elements stolen from tales such as “The Blue Bird,” “The White Cat,” and “Belle-Belle, or the Chevalier d’Fortune.”

For all their popularity and influence in France, however, Madame d’Aulnoy’s tales never quite caught on in English. I suspect this was for a number of reasons. For one, until the 1990s, reliable English translations of her tales didn’t exist. When her tales were translated—and many were not—the 18th and 19th century translators often either drastically shortened the stories (possibly to their advantage) or edited out parts deemed to be offensive or inappropriate for children. Even these edited versions, however, still kept many of d’Aulnoy’s lengthy digressions, or her odd non-sequiturs and awkward conversations—for instance, this unnatural sounding conversation, in English or French, from “The Good Little Mouse”:

“My girl,” said the fairy, “a crown is a very fine thing; you neither know the value nor the weight of it.”

“Oh, yes I do,” the turkey keeper replied promptly, “and therefore I refuse to accept it. At the same time, I don’t know who I am or where my father and mother are. I have neither friends nor relatives.”

For another, many of d’Aulnoy’s tales have something not generally associated with the English tradition of fairy tales, at least as it developed in the late 19th century: decidedly unhappy and sometimes unsatisfactory endings. Even some of her happy endings can be a bit unsatisfactory: as amazing as it to watch Belle-Belle play the action hero in her story, it’s somehow underwhelming to see her marry someone who has done absolutely nothing for her whatsoever except to go along with his sexually frustrated sister’s need for vengeance. Even if he is a king. She captured a dragon (with help) and defeated his enemy, the emperor (also with help) and if you’d asked me, which Madame d’Aulnoy did not, she would have been better off marrying the emperor, the sexually frustrated queen, the lady in waiting who falls in love with her, any of her magical companions. Or the dragon. But in this tale, at least, aristocracy wins out.

But if Madame d’Aulnoy never gained full recognition or popularity from English readers, she had helped to establish the literary fairy tale, as an art form that could be practiced by serious scholars, women, and those in both categories. We’ll keep looking at more of these tales and their letters on Thursdays.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.